The privacy tort of “persona rights” often manifests as an appropriation issue. Someone has value in their personhood that is wrongfully exploited by another and is the tortfeasor is liable for a violation of privacy. As technology evolves and categories, like “fame”, that were more clearly demarcated in previous decades become muddled, it remains to be answered whether laws be able to adequately morph in order to accommodate society’s changing sensibilities. This post will examine the current law, societal changes, and recent examples of this phenomenon in an effort to paint this landscape in broad strokes.

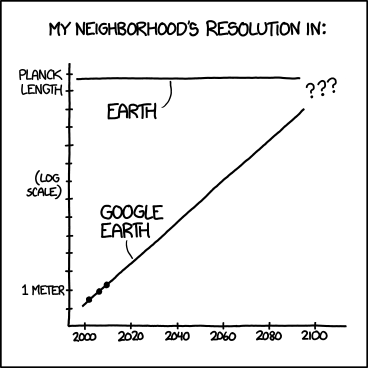

Over the last ten years or so, technology has democratized public speaking platforms. In the past, significant resources were needed to gain access to wide audiences. Today, however, the internet and television have made these audiences much more accessible to common people. While many use this opportunity to advocate for social justice or to educate, some have sought to capitalize on their celebrity aspirations. With the increased numbers of reality television stars and YouTube celebrities, it has become harder and harder to ascertain where celebrity ends and popularity begins. It is therefore equally hard to assess whether an internet sensation has the kind of value/property right that persona rights originally aimed to protect.

This particular privacy action is designed to safeguard the right of the individual to exclusively use his identity for benefit. While the case law on this matter is jurisdiction specific, courts have held that just because you are not a “celebrity” does not mean that your identity has no commercial value. Courts have held that commercial value can lie within a specific group of people even if not within the public at large. Similarly, a defense to a charge of (mis)appropriation of someone’s identity, is a claim that the plaintiff is not a celebrity and therefore has no verifiable worth in their identity.

The tensions discussed above get to the heart of this post. If you do not need to be a “celebrity”, can a quasi-celebrity count? How large of a group is necessary in order for there to be commercial value? Is a YouTube following significant? What about those members of reality television casts who enjoy a brief stint on a popular season of survivor? What counts as proof for commercial value?

Recently, reality television “star” turned business mogul, Kim Kardashian, settled a law suit against Old Navy for allegedly using a lookalike in their ad campaign which violated Kardashian’s publicity rights. While Kim may demand big bank for her stamp of approval on a clothing retailer’s threads, other reality tv stars may not be so highly thought of. Perhaps the best approach to this is to examine whether the misappropriated use either would have earned the plaintiff money if they had used their identity in that way or whether they generally engaged in that kind of commercial use of their identity.